Many IELTS candidates struggle with Reading Passage 3. The topic feels academic. The vocabulary sounds abstract. The argument builds slowly, and the matching headings or true/false questions become harder to navigate. If you faced a similar difficulty with Passage 3 in the Cambridge 15 Test 1, you are not alone. This passage, titled “What Is Exploration?”, requires you to track a complex idea about how the definition of exploration has changed over time. This blog breaks it down paragraph by paragraph so that the core message becomes clear. Difficult words are explained. Arguments are simplified. The goal is to help you read smarter, not longer.

What does the passage try to say overall?

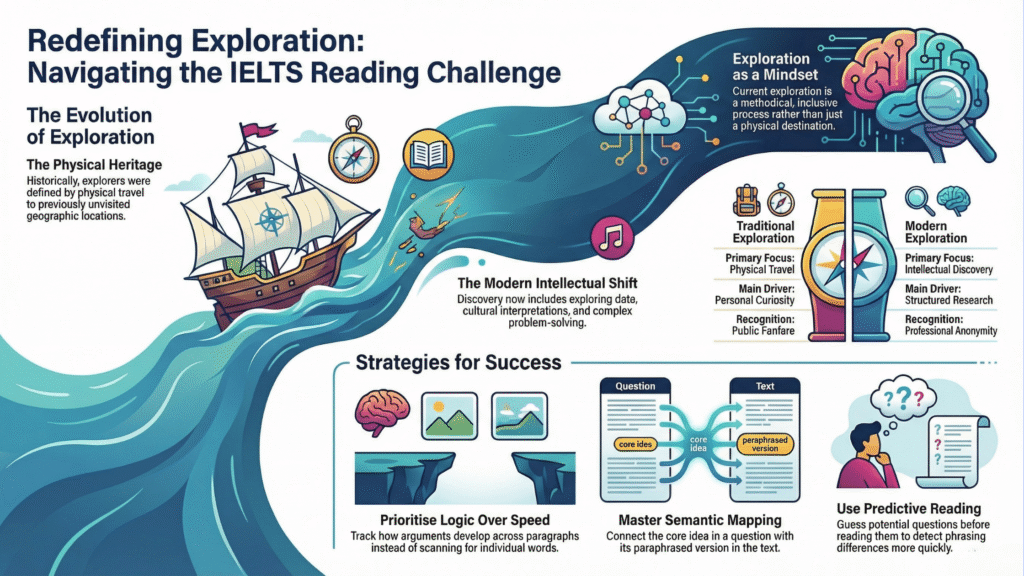

The passage explores how people have defined the word “exploration” across different periods in history. It starts with traditional explorers like Christopher Columbus and ends with modern examples like space missions or digital discoveries. The writer wants to show that exploration is not only about physical travel. It can also be about thinking in new ways or interpreting information differently. This shift from physical to intellectual exploration is the main idea that connects all paragraphs. Once you understand this shift, the matching headings and summary completion questions become easier to solve.

Paragraph 1 explained in simple terms

The opening paragraph introduces Michael Collins, one of the Apollo 11 astronauts. While Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon, Collins stayed in orbit. The writer says Collins was “the loneliest person in history”. But instead of praising this loneliness as heroic, the paragraph asks whether this kind of exploration still feels relevant. The paragraph questions whether being physically alone in space automatically makes someone an explorer. This sets up the theme. The writer is asking us to think more deeply about what “exploration” really means today.

Key word explained:

- “Reassessment” means thinking again about something and questioning earlier assumptions.

Paragraphs 2 and 3: Who decides what exploration means?

These paragraphs discuss how the media and the opinion of the people contribute to defining who we refer to as an explorer. According to the author, explorers such as Columbus or Scott were considered to be the explorers in the past because they visited places that had not been visited by other people. However, nowadays, the opinion is not always unanimous. The media can declare someone an explorer depending on the dramatic nature of his/her journey or the suitability of the journey to a story. The same paragraphs also state that there are individuals who refuse to be called explorers when they believe that they are dated or no longer relevant to their mission.

Key word explained:

- “Frivolous” means not serious or lacking depth. Used to show how some media-driven labels feel shallow or exaggerated.

Paragraph 4: The shift from physical to intellectual journeys

This paragraph introduces a new direction. It says modern explorers may not travel far but explore ideas, data, or culture. The example of John Harrison is mentioned, a man who never sailed but made sea travel safer through his invention. This paragraph is key because it expands the meaning of exploration. It argues that exploration can also mean solving complex problems. You do not need to stand on a mountain. You can work quietly and still be exploring something important.

Key word explained:

- “Cultural interpretation” means understanding or explaining how people live, think, or behave.

Paragraph 5: How funding and science have shaped exploration

This paragraph talks about how science and business now influence who gets to explore. Scientists explore data. Investors explore markets. The process is planned and funded. The writer says this is different from earlier forms of discovery, where exploration was driven by personal desire or curiosity. Now it often comes with goals, reports, and outcomes. The message is not negative. The writer simply wants to show how the meaning of exploration has moved from adventure to structured research.

Key word explained:

- “Methodical” means careful, planned, and based on a clear system.

Paragraph 6: Public recognition and the modern explorer

The writer asks whether today’s explorers feel satisfied with their work if no one celebrates them publicly. This paragraph connects to an earlier idea that public recognition once defined explorers. Now, many people explore without media coverage. Scientists, historians, and even artists work for years without fanfare. Their contribution is real, but the label of “explorer” is rarely used for them. The writer suggests this is a cultural gap. We may need new words or new ways of valuing intellectual journeys.

Key word explained:

- “Anonymity” means being unknown or not recognised publicly.

Final paragraph: Redefining exploration without dismissing the past

The last paragraph brings the argument to a calm close. It does not say older definitions were wrong. It says the idea of exploration should grow. We can still respect physical adventurers while also making space for those who explore data, history, language, or technology. The writer wants the word to be more inclusive. Exploration, they argue, is a mindset, not a location.

Key word explained:

- “Inclusive” means welcoming different types, not limited to one format or group.

Why does this passage feel difficult for many test takers?

This passage is not based on facts or definitions. It is based on interpretation. That means you have to track how the idea develops across paragraphs. Many students get stuck on words like “reassessment”, “cultural lens”, or “interpretation of meaning”. Others lose time trying to memorise all the explorer names. The questions often focus on identifying shifts in meaning or matching paragraph summaries. If you do not understand the tone, you may choose a heading that seems right but misses the writer’s argument.

What should you do before answering the questions?

Before solving the questions, read the topic sentence of each paragraph. Ask yourself what that paragraph is doing: introducing, contrasting, expanding, or concluding. Use this to match headings. When solving True/False/Not Given, keep in mind that “Not Given” means no opinion is offered, not that the fact is untrue. For sentence completion, return to the exact phrase in the passage. Look for grammar clues. Do not guess based on the topic alone. The Reading test rewards those who track ideas, not just words.

How does Shane Jordan teach this passage at InSync?

Shane Jordan focuses on building logic before speed. He does not ask students to finish fast. He asks them to think in steps. His method is based on real IELTS scoring logic. As a former IELTS examiner with over twenty-four years of teaching experience, Shane shows how each paragraph has a job. He explains how to read for argument rather than for information. This works well for passages like “What Is Exploration” because the main challenge is tone, not fact. His sessions at InSync build calm reading habits and accurate paragraph tracking.

What to do if you still struggle with Reading Passage 3?

If you find yourself stuck at Band 6 in Reading, the problem is usually not vocabulary. The problem is logic. You read everything, but cannot decide what the writer is really saying. The solution is not more practice. It is a guided correction. At InSync, Reading modules are broken into skill steps. You learn how to spot key lines, how to separate fact from opinion, and how to match tone with question style. With weekly feedback and question breakdowns, you stop guessing and start recognising patterns. That is how you cross the Band 7 line.

Challenge 4: The Paraphrasing Puzzle – When Questions Use Different Words Than the Text

The Problem:

IELTS Reading questions are built to test meaning recognition through paraphrasing instead of word-for-word spotting. This causes major trouble during Matching Headings and True/False/Not Given tasks. For example, students may keep searching for “economic prosperity” inside a paragraph that only mentions “financial well-being.” That becomes a blind spot.

Chennai students often rely on matching exact phrases due to school-level question formats. But IELTS avoids those formats entirely. Examiners replace vocabulary, shift sentence structure, and test your ability to connect the dots between phrasing and intent.

Why This Happens:

Most school reading questions reward word-matching. If a paragraph says “plants need sunlight,” the question also says “sunlight is needed.” IELTS breaks this pattern. It uses synonyms plus grammar shifts to test deeper reading.

This skill is called semantic mapping—the ability to detect meaning links between different expressions. Without exposure to varied texts, that recognition stays underdeveloped. Students then feel lost when questions use unfamiliar words for familiar ideas.

Vocabulary strength alone is not enough. You also need to see how grammar shifts impact sentence interpretation. That is what makes paraphrasing difficult under time pressure.

Required Reading Sub-Skills:

Synonym Recognition:

You must identify common academic synonyms quickly. For example, benefit pairs with advantage, while challenge connects with difficulty. You need to develop these links across IELTS topics.

Conceptual Paraphrasing:

You must recognise when two very different sentences express the same point. For example, “scientists discovered something” and “a discovery was made by scientists” convey the same idea.

Semantic Mapping:

This skill connects the core idea in a question with its corresponding version in the passage. It involves filtering sentence structure, word form, and logic under time pressure.

Strategic Solutions:

Build a Theme-Based Synonym Bank:

Create a notebook arranged by common IELTS themes such as health, economy, technology, environment, and education. Write down core words along with synonyms. For example, under “Environment,” list: pollution plus contamination, conservation paired with preservation, and sustainable along with eco-friendly. Expand this bank weekly.

Practice Rewriting Paragraphs in New Words:

Choose one paragraph from a Reading test. Then rewrite it entirely in your own words while keeping the meaning intact. This reverse engineering helps build recognition when examiners paraphrase key ideas in difficult ways.

Apply the Matching Headings Breakdown Strategy:

Before reading, paraphrase each heading into simpler words. Then read the paragraph while focusing on the first and last two sentences. These sections usually contain the main idea. Match the heading to that core message, not to one repeated word.

Use Prediction to Improve Paraphrase Spotting:

Before looking at the actual questions, read the paragraph and guess what questions could be asked. Then compare your guesses to the real questions. This rewires your brain to detect phrasing differences faster during exams.

Learn IELTS Grammar Transformation Patterns:

IELTS often changes voice, form, or expression. Active voice becomes passive. Nouns become verbs. Adjectives shift to adverbs. Examples include:

- “Researchers conducted the trial” becomes “the trial was conducted by researchers.”

- “Rapid growth” becomes “grew rapidly.”

- “Education reform” becomes “reforming the education system.”

By learning these grammar shifts, you increase your speed and confidence with paraphrased questions.